When drawing from academic work that traces forgotten histories, we can learn much about Brighton’s past.

But as we build a picture of the town 200 years ago we should strive for accuracy – and remember the extraordinary part played by its people.

Brighton was an abolition town. Archive copies of the Brighton Gazette and the Brighton Guardian offer a glimpse of the anti-slavery attitudes of its people.

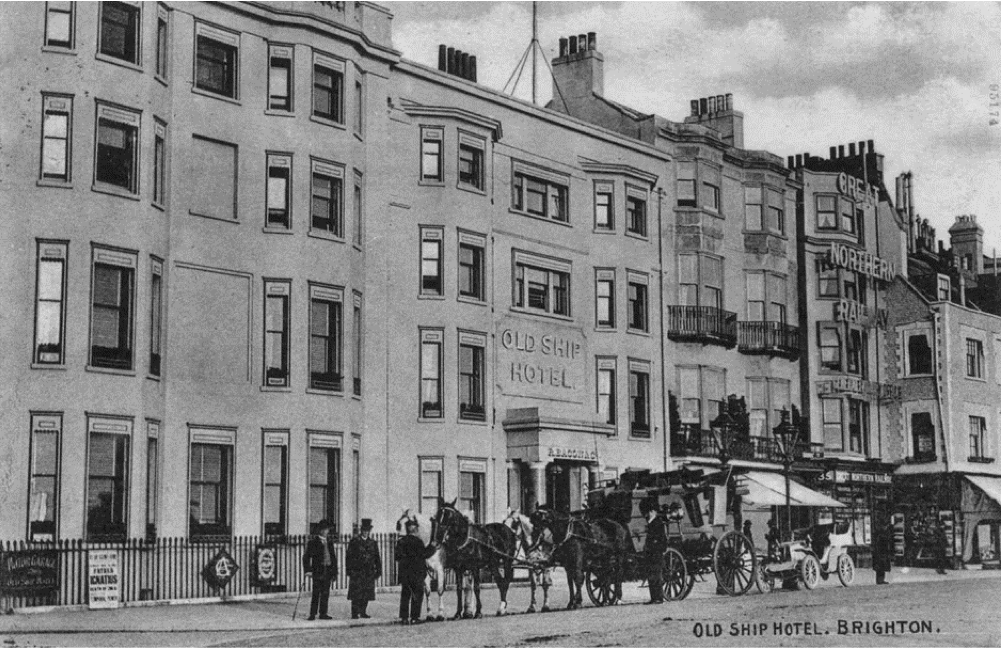

In the 1820s and 1830s it seems that the Old Ship Hotel, in Ship Street, hosted numerous public meetings on the issue of abolition.

A short distance away, at the Friends’ Meeting House, Quakers hosted similar gatherings.

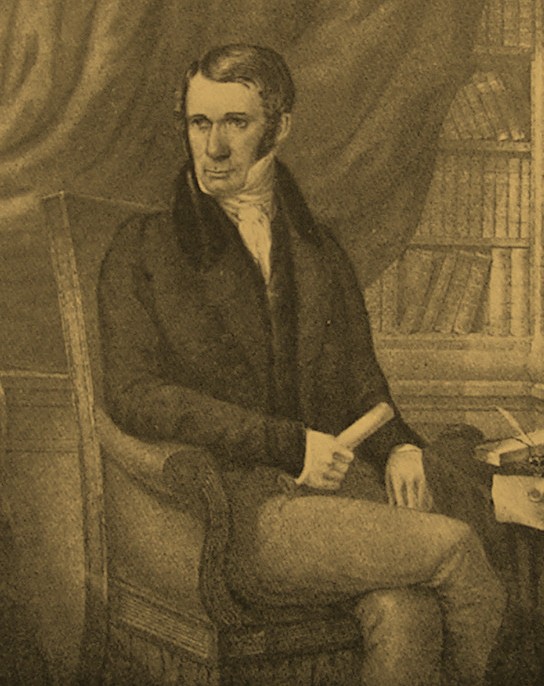

George Faithfull, a non-conformist preacher at the Ship Street Chapel (later renamed Holy Trinity Church), was resolute in his anti-slavery campaigning.

Propelling the abolitionist views was an 1824 pamphlet called “Immediate not Gradual Emancipation” by Elizabeth Heyrick.

Her call for a nationwide boycott of West Indian sugar had spurred Brighton grocery stores to lead the way by refusing to stock it.

The Gazette reported that on Tuesday 16 November 1830, at 6.30pm, despite “the tempestuous state of the weather”, an anti-slavery public meeting took place at the Old Ship.

It was agreed that a petition would be submitted to “the legislature” resolving that slavery was “repugnant to justice, humanity and sound policy (and) to the principles of the British constitution and to the spirit of the Christian religion”.

The meeting voted to form the Brighton Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and decided that demand in the town and its vicinity was sufficient for the formation of an anti-slavery “ladies society”. Brighton grocer Isaac Bass proposed the motion.

As fascinating and uplifting as these historical snippets are, they feel eerily relevant to the city in 2020.

In early June, council leaders were quoted in the press suggesting that the city was built on the profits of slavery.

Some stretched the historical record to imply Brighton and Hove’s Georgian buildings owe their very existence to the slave trade.

The integrity of the historical record depends on facts. It is certainly a fact that in 1836 the British government began paying out £20 million (about £16 billion today) in compensation to 46,000 British slave owner claimants (or beneficiaries of slave owners listed in a will) as “recompense” for losing their “property”.

Many had already grown rich on the profits of the trade and now grew obscenely richer as a consequence of abolition.

Of those compensated, a search of the “Legacies of British Slave-ownership” database set up at University College London (UCL) reveals 19 people – receiving a combined total of £153,422 (about £17 million today) – as having an actual Brighton address.

It goes without saying that 19 out of 46,000 British nationals compensated is a tiny number.

As for the wealth that “built” Brighton, local historian Peter Crowhurst points out that there is no consensus among historians on the extent of the impact of slave trade profits on the British economy.

There is, though, no doubt that the nation’s increasing dependence on sugar and cotton meant the nation benefited enormously from slavery.

Certainly, the initial wave of Brighton’s development, which took place between 1790 and 1820, occurred too early to have benefited from any finance derived from the compensation payments.

More broadly, if we were to trace the links between the nation’s historic buildings, the money that built them, the wealthy people who once lived or worked inside them and the capital accrued from Britain’s imperial conquests, it would result in a crime-map covering the length and breadth of the land.

In the case of Brighton’s links with any slavery profiteer developers, historians identify just one – a Mr JB Otto, who owned a West Indies plantation and built Royal Crescent in Kemp Town from 1799 to 1801.

Otto doesn’t appear on the UCL database (by 1836 he had either died or sold his interests).

However, academics at Brighton University seem to imply a far greater complicity between the city’s built environment and the profits of West Indies slavery.

Pondering the significance of the Royal Pavilion’s Orientalist architecture (and its architectural references throughout the city), the Brighton University academics argue that this “colonially derived exoticism” obscures the wealth derived from slavery.

This wealth, “extracted from the other side of the Atlantic”, also “congealed”, say the academics “in the city’s brick and flint”.

Their essay does uncover fascinating and moving stories. The sections on the 1831 Tortola rebellion and Brighton resident and plantation owner Caroline Anderson, on Elizabeth Heyrick, Isaac Bass and the Old Ship abolitionists all make essential reading. But it offers no further detail on its “brick and flint” assertion. This is a shame.

The essay’s utilisation of the UCL database and its focus on Brighton is indeed the source of those comments made by council leaders in June.

As such, the stance taken by council leaders was inaccurate and unnecessarily divisive.

Perhaps, in 2020, a more unifying message would be to note that living amid a Georgian town (developed courtesy of a range of wealthy investors) were actual, living citizens who contributed heart and soul to the fight against slavery.

When they met – in the Old Ship, the Friends’ Meeting House, the Ship Street Chapel and in many other locations – they demonstrated the decency of ordinary people.

Arguably it was Britain’s imperial interests that lay behind the abolition movement. By the early 1800s the slave trade was less important and so, through the role given to William Wilberforce, taking the moral high ground served those needs far better.

But in Brighton the radical mood appears far closer to Heyrick’s militant demand for immediate emancipation and influenced by the likes of former slave turned abolition campaigner Ottobah Cugoano.

Some might say Brighton’s “Ship Street” radicals were small in number – that, really, a more apt characterisation of the town would centre on wealthy slave traders and an indifferent or complicit mass of townsfolk (that, collectively, the city of today should be ashamed of its past).

However, another historical snippet suggests such a characterisation would be wrong.

On Thursday 13 December 1832, the people of Brighton elected their own Members of Parliament for the first time.

In fact, the two MPs they elected were radicals – persons known to the town as holders of extremely liberal ideals.

They supported, among other things, the abolition of “unmerited pensions and sinecures”, the further widening of the right to vote and … you guessed it, the abolition of slavery.

One was Isaac Newton Wigney, son of a local banker. The other was the non-conformist preacher of Ship Street, George Faithfull.

In 1832 the right to vote was still highly limited. Nonetheless, those who lent their vote to the anti-slavery, pro-democracy radicals Wigney and Faithfull were just the tip of the iceberg.

It was a voter turnout that spearheaded the hunger for social justice and universal suffrage that would soon animate the Chartist period to come.

For Brighton’s citizenry, the fact that Britain’s ruling elite had profited from slavery and now resisted extending the franchise to every man and woman was indeed repugnant.

Reminding ourselves of any links Brighton had with the transatlantic slave trade is no bad thing. But too often the past is selectively plundered to make a political point (however well-intentioned that point might be).

When tracing forgotten histories let’s be sure to tell the stories of everyday citizens who lived and worked here, who held extraordinarily liberal views for their time and who campaigned tirelessly for the immediate abolition of slavery.

Adrian Hart is a neighbourhood activist living in east Brighton. He is author of That’s Racist! – How the regulation of speech and thought divides us all.

This article first appeared on the Brighton Society website where the original can be read with footnotes. It is reproduced with the permission of the Brighton Society and the author.

No one living in B&H should feel ashamed of past slavery. We are not those peolple and are not responsible for their actions. History should guide not enslave us..

In this period of time, a very small percentage of the population had any influence. Women were also considered property and were not even allowed to vote for over a hundred years. The working class lived in abject poverty and were subject to many privations including lack of sanitation and exposure to all sorts of illnesses. Death rates were much higher.

Slavery was a terrible episode in the history of humanity but it was no joy either for the masses. The Irish potato famine had also not yet occured with all the miseries yet to be endured