A strange tone surrounds the debate about giving 16 and 17 year olds the vote. It’s pretty incongruous to a middle-aged bloke like me so God knows what it’s like through the eyes of young people’s themselves.

Whenever you mention the idea, politicians who spend most of their time on TV saying how brilliant, bright and talented young people are suddenly start slagging them off.

They’re too immature, not experienced enough, aren’t capable of understanding things or their lives are too dominated by one institution to vote on broad issues.

The list goes on and on, oblivious to the fact that every accusation could just as easily be levelled at elements within every demographic.

The least we could do is be even-handed. If maturity is a qualifier to vote, the Foreign Secretary should be disenfranchised without delay.

If life dominated by one institution, such as schools for young people, is just too much, what about people whose lives are spent in the military or in a care home. Should they lose the vote too?

I have a different approach. I simply believe that we as a society are missing out on the insight, experience and wisdom of young people – and our body politic and policy outcomes are suffering for it.

Voting at 16 is one of those things that sounds so much more radical than it actually is. Today only a minority of 18 year olds actually have the right to vote in the course of an election cycle.

If this parliament goes the full term to 2022, for example, every youngster who turns 18 at the moment will be well into their twenties by the time they can vote for the first time.

The same would be true for 16 year olds, for whom unless there is a general election every year – God help us – only around 20 per cent will ever be eligible to vote at that age.

I’ve introduced a bill to parliament with Nicky Morgan MP and Norman Lamb MP. It does three things.

First, it enfranchises 16 and 17 year olds. Second, it auto-enrolls young people on to the electoral register. And finally, it places polling stations in educational establishments.

It’s a bill that doesn’t just allow young people to vote, it strives to extend the privilege of voting to a democratically hard-to-reach place.

Considering the setting, support and access to learning and information, I truly believe that they will be the most informed part of our electorate.

And we know from evidence that voting at the first opportunity sets in train a habit that lasts a lifetime.

The challenge now is to unlock the clear majority there is in the Commons.

Now that there’s a smattering of Scottish Tory MPs, it’s becoming absurd that the Prime Minister accepts that 16 year olds are capable of voting for council, Scottish Parliament and in a Scottish independence referendum but don’t have what it takes to decide who to send to Westminster.

Soon Welsh 16 and 17 years olds will have the same rights so the grim job of explaining to English kids that they can’t have the same rights as their Scottish and Welsh friends will fall solely to Tories.

And what a stupid place that would be to park your politics in an era of hung parliaments where every vote matters.

The problem with conservatism in any party is the apathy it generates. I’ve heard from all quarters that “it’s inevitable I suppose but it’s not something I’m really bothered about”.

Well I am bothered. I want to live in a democracy that strives to push the limits of inclusion, not one that hides behind cynicism as a means to be exclusive. Allowing more young people to vote is an old idea whose time has finally come.

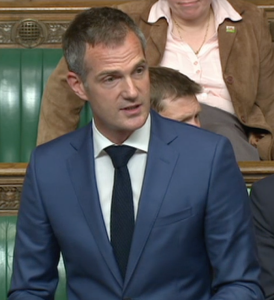

Peter Kyle is the Labour MP for Hove.

The last time the voting age was reduced – by a Labour Government – the Tories won the next General Election. In fact, after that, it took until 1997 for Labour to win a working majority. It’s an admirable idea, but it may backfire on Labour, which is the Party keenest on this idea.

The concept of no taxation without representation has its converse: no representation without taxation. Voters should at least be liable to taxation, even if they are unable to work through illness, disability or unemployment. Those still required by law to be in full-time education will not be paying income tax, national insurance or council tax. They are also unlikely to be paying rent or for a mortgage. These are not the only considerations, but they are not inconsequential.