Brighton hospital bosses unfairly sacked a black consultant having made it impossible for him to return to work, an employment appeal tribunal judge said yesterday (Thursday 29 June).

Brain surgeon James Akinwunmi had previously told an employment tribunal that NHS emergency patients were turned away while fellow neurosurgeons, who were on call, treated private patients.

And he said that other consultants fraudulently claimed double pay but his complaints about this were ignored by bosses at Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust (BSUH).

Instead, Mr Akinwunmi, a former Formula 1 doctor, said that his bosses and colleagues had closed ranks and forced him out.

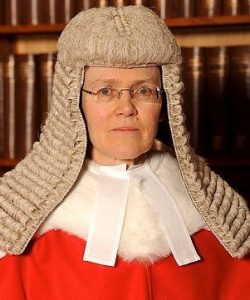

Employment appeal tribunal judge Elisabeth Laing noted that the trust, which runs the Royal Sussex County Hospital in Brighton, had previously settled a claim for racially discriminating against Mr Akinwunmi.

And yesterday she upheld the verdict of the earlier employment tribunal after BSUH appealed against its finding of unfair dismissal.

The employment tribunal had rejected Mr Akinwunmi’s claim of victimisation and did not accept that he had suffered as a result of whistleblowing. But it did find that he had been unfairly dismissed by the Brighton trust.

Trust bosses appealed against the original finding of unfair dismissal, calling it a perverse decision. They said that Mr Akinwunmi had contributed to his dismissal by being off work for nearly two years.

Part of this absence was for an unpaid sabbatical. The sabbatical was planned by Mr Akinwunmi and approved by the trust although they had made it hard for Mr Akinwunmi by unreasonably interpreting the trust’s sabbaticals policy to his detriment.

Trust bosses then mishandled the poor relationships between Mr Akinwunmi and his colleagues, which worsened in his absence, making it impossible for him to return to work after his sabbatical ended.

Judge Laing accepted the employment tribunal finding that trust bosses had not dealt with the hostile and toxic work environment facing Mr Akinwunmi and she threw out the trust’s appeal.

Mr Akinwunmi had behaved reasonably, she ruled, unlike those in charge of the Brighton hospital trust.

One exception to her criticism was a plan to address some of the problems which had been set out by former acting chief executive Chris Adcock who has since left BSUH.

And an analysis by former trust executive Adrian Twyning was accepted and his recommendations, including mediation, were “extremely well made”, but key elements were not acted on by the trust. Other external advice was also ignored.

Mr Twyning’s analysis found “a culture of poor working relationships, ineffective communication and low levels of trust”. The employment tribunal said: “He feared it would affect patient care, safety and the effective running of the department.”

Mr Twyning recommended a separate investigation into claims of bullying and discrimination by neurosurgeon John Norris. The employment tribunal said: “The report strongly supported formal management training for (Mr Norris) and equality and diversity training for all medical staff in the department.”

Judge Laing highlighted general criticisms made by Judge Christiana Hyde after she heard the original claim at the London (South) Employment Tribunal.

Judge Laing said: “Many of the (Brighton hospital trust’s) important documents were not shared with (Mr Akinwunmi) at the time when they were generated, and, indeed, some did not emerge until they were produced in the course of the hearing, in some cases after the relevant witness had given evidence.

“Some of the (Brighton hospital trust’s) witnesses did not make a good impression on the employment tribunal.

“The employment tribunal used the word ‘disingenuous’ and its cognates several times when describing their evidence.”

As well as BSUH, the original employment tribunal case had been brought against five neurosurgeons – John Norris, Carl Hardwidge, Lal Gunasekera, Giles Critchley and Sorin Bucur.

Judge Laing quoted from the employment tribunal judgment when Judge Hyde had given “yet another example of the consultants failing to deal with (Mr Akinwunmi) in a rational and professional way”.

They had made complaints about him without any personal knowledge, she said, and they tended to “shoot from the hip”.

In particular Mr Norris and Mr Hardwidge had driven unfounded and “mischievous” complaints against Mr Akinmunwi after the consultants had held many “corridor conversations”.

The consultants had tried to paint a picture of Mr Akinwunmi as incompetent on the basis of one error in 10 years of surgery – and despite their insinuations it was an error that Mr Akinwunmi had himself openly and properly reported.

Judge Laing said: “The employment tribunal therefore accepted (Mr Akinmunwi’s) claim that the five consultants had made spurious allegations with no factual foundation. But that part of (Mr Akinmunwi’s) claim was out of time.”

Judge Laing’s ruling repeated the employment tribunal criticisms of Mr Norris for trying to pretend that Mr Akinwunmi had unilaterally withdrawn a complaint of racial discrimination.

In fact the trust had accepted that Mr Akinwunmi had been discriminated against and had settled his claim – and Mr Norris had personally signed an agreement as part of that settlement.

Mr Norris had misrepresented the situation to others and had given “rather misleading” and “disingenuous” evidence on other points to the employment tribunal.

All these factors contributed to a toxic working environment – and Mr Akinwunmi was reluctant to return after his sabbatical for personal health reasons and over proper concern for patient safety. He was suffering from stress as a result of the actions of his five colleagues during his sabbatical.

Judge Laing said: “The employment tribunal said (and this is an important finding) that the respondent (BSUH) should have taken responsibility for improving the working environment.

“The fact that matters had got to this stage reflected extremely poorly on (BSUH’s) management.

“It was clear (BSUH) had known about the breakdown of working relationships for a long time and there was no evidence of any efforts to improve them.”

The trust was criticised for inconsistency, disingenuity and unfairly keeping Mr Akinwunmi in the dark about key matters.

It was little surprise amid all the recriminations and in-fighting that “there were uncontrolled waiting lists” – and at one point the hospital trust “decided to close its neurosurgery service to all new patients for six months”.

Mr Akinwunmi was also rightly concerned that it would be unsafe for him and his patients were he to return to work. And it was, Judge Laing said, a reasonable position because of those safety concerns.

James Akinwunmi is practicing in Grand Cayman and his website states that he is licenced to practice in the United Kingdom and has a practice in Harley Street. This is not true.

https://www.spines.com/surgeons/dr-james-akinwunmi

The GMC website states “Neurosurgery From 12 Mar 2002 but is not currently licensed to practise”

to Frank le Duc

I had my long awaited neurosurgical operation cancelled on the 19 Sept after being called in at 7:30 on the day. Mr Mansoor Foroughi was ready and keen to operate the theatre booked and back up staff waiting in place. Two hours later after all the preliminary paperwork and checks done to the satisfaction of the medical team I was told no BED and sent home. As a patient now awaiting neurosurgery at BSUH for 18 months I am most concerned to read the above article. I am told that 50% cancellation on the day is usual!!! I am due to undergo this procedure again on Monday 9 Oct. Its looking like all the political nonsense is still ongoing!!! I am very low and dreading yet another cancellation on Monday.

Please advise c Honyben